For several months now, I have been contributing to The Jakarta Post with a colleague, friend, and boss of mine, Kayee Man. After a while we thought that maybe not many people read our articles, as we got very few responses from our readers. But some days ago, I checked my office email address, which is forwarded to my personal email, and found an email that was sent back in July 2006 and apparently got into my personal email’s ‘spam’ folder because it had no subject.

The email was both pleasantly surprising as well as rather shocking because the sender was none other than the author of “Creative Economy”, John Howkins, who read one of our articles “But … That was My Idea” and wrote a rather angry email saying that we were wrong in that ideas should not be owned. Apparently Howkins is also the president of Adelphi Chapter, which aims to “ensure that everyone has access to ideas and knowledge, and that intellectual laws do not become too restrictive.”

Baffled by the thought how our ‘neutral’ article could trigger such a strong response from author of a book we quoted, I responded to Howkins’ email asking him why according to him ideas should not be owned, because clearly authors (of books, articles, designs, ideas) would like to and should get credits for their intellectual brainchild. So where is the misalignment?

I explained to Howkins that in Indonesia, respect for authorship of ideas and due credits for authors could not be over emphasized. The international copyright law is highly abused in Indonesia because Howkins’ book, for example, costs more than a sixth of minimum salary in Indonesia – which makes his book and most imported books highly inaccessible for most members of this society. If the international copyright law isstrictly maintained in Indonesia, very few could have access to development of ideas and knowledge from other countries.

This ‘inadequacy’ and ‘casualness’ about copyright of books, however, in my opinion should not extend towards ‘inadequacy’ and ‘casualness’ about copyright of ideas. In Indonesia most people are rather casual about authorship of ideas that plagiarism can be found in many forms.

But it is difficult to blame it on anyone coming out of Indonesian conventional education to know that we are supposed to write down the name of the people we quote and the sources of our quotations. How could we when we are often asked by our teachers to write about a reading without having to differentiate whether what we write is our own thoughts and interpretations of the reading or simply rewording or even blatant copying from the book.

What I learned, though, is that most people – even the very famous ones – would gladly share their ideas, presentations, or even workshops if only we ask them politely and credit them properly in our adaptations. Giving people their due credits not only promote 'good work' but improve your own credibility as a person.

Similar to how my stance in this matter is originated and influenced by my own background and the society I’m living in, it seems that Howkins’ stance in this matter seems to likewise originated and influenced by his own background and environment.

Kayee (English-born Asian) noted that prominent English education leaders seem to have this inkling towards patenting their ideas. Examples of them being Edward deBono (famous for his Six Thinking Hats and Lateral Thinking) and Tony Buzan (famous for his Mind Map), who both attach their personal names to their expression of ideas, profit from trainings and have endorsed trainers to distribute their ideas.

Compare them for example with prominent American education leader like Howard Gardner(famous for his Multiple Intelligences) whom has website through which you can download some of his papers – for free. No wonder Howkins is so adamant about too restrictive ownership of ideas.

Wednesday, January 31, 2007

On Motivation and Excellence

On Monday, I met with my students from last semester and chatted a bit. Two issues came up.

The first one is their confession that they are unmotivated this term – to whom I would refer to “Incentive to Learn” posting, which may not change their motivations, but I hope would make them think twice and realize that education is a shared responsibility.

The second issue has to do with what I would refer to as the drive to excel. Because of lack in time they have for designing, they mentioned that many of them ended up doing it just for the sake of completing the assignment (and get it over with). One of them unconsciously ended up with similar detail, although her intention was different.

Both issues make me think about what makes people tick. What makes (some) people have the drive to excel? What makes (some) people try to push themselves further and better (when it is probably easier to repeat after their own or even after other people’s successes without anyone else ever find out) despite the fact that perhaps few people other than themselves would notice any difference or even progress? What makes (some) people try to be ethical and do 'good work'?

I thought the answer has to do with an article I co-wrote a while back: Drive to Excel. But perhaps there is more to this.

The first one is their confession that they are unmotivated this term – to whom I would refer to “Incentive to Learn” posting, which may not change their motivations, but I hope would make them think twice and realize that education is a shared responsibility.

The second issue has to do with what I would refer to as the drive to excel. Because of lack in time they have for designing, they mentioned that many of them ended up doing it just for the sake of completing the assignment (and get it over with). One of them unconsciously ended up with similar detail, although her intention was different.

Both issues make me think about what makes people tick. What makes (some) people have the drive to excel? What makes (some) people try to push themselves further and better (when it is probably easier to repeat after their own or even after other people’s successes without anyone else ever find out) despite the fact that perhaps few people other than themselves would notice any difference or even progress? What makes (some) people try to be ethical and do 'good work'?

I thought the answer has to do with an article I co-wrote a while back: Drive to Excel. But perhaps there is more to this.

Sunday, January 28, 2007

Eviction is the ‘Solution’

An article in Kompas January 23, 2007 entitled “Mimpi Buruk Setelah 28 Tahun” (Nightmare after 28 Years), featured an eviction of 136 houses and 200 kiosks in Pedongkelan, Kelapa Gading area by some 1500 government officials. The area was illegally turned into vendors’ market some 28 years ago, and now with the plan to turn it into a flyover, the buildings were bulldozed over, leaving many inhabitants lose not only a place to live, but a place to earn a living.

Another article in Kompas January 26, 2007 reported another eviction of 432 families (around 2000 people) living under the highway in Penjaringan.

...

With the persistence of eviction by the government of Jakarta, it seems indeed that eviction has become the one ‘solution’ to overcome the bigger problem of rights for living and working in a city that should be made possible for all. Yet, is eviction a ‘solution’?

Read full posting here.

Another article in Kompas January 26, 2007 reported another eviction of 432 families (around 2000 people) living under the highway in Penjaringan.

...

With the persistence of eviction by the government of Jakarta, it seems indeed that eviction has become the one ‘solution’ to overcome the bigger problem of rights for living and working in a city that should be made possible for all. Yet, is eviction a ‘solution’?

Read full posting here.

Tuesday, January 16, 2007

Between Bangkok and Jakarta

As I walked through Khao San Road in Bangkok for the first time, I was mesmerized by the hustle bustle, lively ambience of the street: highly energetic yet relaxed, radiantly foreign yet subliminally familiar. As part of a half-day trip organized by the International Association for the Studies of Traditional Environment (IASTE) conference, I only had a little more than an hour to savor in this exuberance of urbanity. This vivacity, however, occurred only at the street level. Hovering above is the eerily empty old shop houses with dilapidated woods, peeled off paint mixed with layers of dust, one brightly colored billboard sign after another, merging inns, internets, cafes, tours and travels, English and Thai characters, and all the colors and ages of the people walking and sitting idly beneath them.

Granted, this brief observation through a tourist lenses could very well be loaded with urban problems in its day-to-day reality. Nevertheless, a quite thought emerged: architectural design did not seem to matter in urban spaces such as Khao San – or did it? Could this organically, informally created spaces be replicated formally through architectural design, or would such an attempt be labeled as yet another hyper-reality so overly discussed during the IASTE conference?

The day after, I presented my paper about Jakarta: the epitome of a privatized metropolis where long term planning of public amenities are neglected and sacrificed on behalf of short term, high-profit generating projects. In contrast with my short-lived experience in Khao San, my reading of Jakarta presented a grim image of the city divided by socio-economical classes and ethnic groups, disjointed areas and experiences that represented a demarcated society – neglectfully constructed out of casual everyday journeys around the city.

The government-planned public transportation system, focusing more on monumental constructions as means of creating an “imagined community” (Anderson, 1990), could not keep up with the demand of vast urban sprawl and population growth of the city. Instead, the patchy networks of privatized public transportations and the organically developed informal ones took over. For the privileged, the use of private vehicles became the choice, contributing to unnecessary exertion of human energy, economically inefficient traffic congestion and environmentally degrading pollution. The privatized public transportations also catered to more commercially viable areas – neglecting poorer, left over areas of Jakarta.

The informal communities, being abandoned by the formal and privatized systems, had constructed their own networks that to date had not been adequately addressed in planning and design of Indonesian cities and public places. This informal public transportation system, and to certain extent the privatized ones, created a haphazard network with a logic of their own – one that, if only partially and tentatively, resembled a rhizome, or nomadic logic, described by Deleuze and Guattari. They stood in opposition to the state, or striated logic, of the planned and formal public transportation system (Deleuze & Guattari, 1987).

How can informal community, system, and network be incorporated in formality of planned and privatized cities when they seem mutually incompatible? What makes one informality, as in the case of Khao San, different from the informality as in the case of Jakarta? What are the contributing factors to successes and failures of informalities? And in what ways do communal values affect the making of spaces and conversely, how could spaces affect the making of communities?

This is the first in a series of posts on my comparative study between Bangkok and Jakarta, initiated by Institute for Ecosoc Rights and funded by UNDP Partnership. See here for Sri Palupi's view of the same topic.

Saturday, January 13, 2007

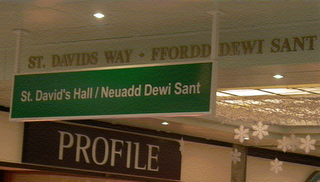

The Profile Image

Finally I found the perfect image for my profile! I came across these set of signs in Cardiff: apparently Dewi is Welsh for David. Coincidence? I think not. It’s just that some society, somewhere got it completely right! :) So if you keep looking for something, somehow, somewhat, somewhere, you will find it.

Sunday, January 07, 2007

Crossing Borders

I left Bangkok yesterday for Cardiff, UK to present in another conference – this time on creativity in higher education. After thinking mostly about spaces and the fights among different stakeholders for spaces in the past few weeks, the shift in mind set will have to come in faster than the jetlag between continents. Meanwhile, other shifts that I must adapt to present itself along the way.

Un-halted stroll straight into the boarding area in Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport (even after the New Year’s Eve’s bomb), in contrast with going through two highly secured posts in Singapore’s Changi Airport: one right off from the plane (What were they thinking? That someone would bring a bomb all the way across continents without being noticed by security guards in other continents to bomb Singapore?) And another before going into the boarding area.

Or maybe I’m already spoilt by the laissez-faire attitude towards security in Bangkok – where I can just stroll in and out of places without once going through metal detectors or security checks that can be found in most of Jakarta’s places. But the security in Changi makes the ones in Jakarta look like a joke (which is true most of the time: they are just put up for shows only). At Changi, you would have to take off your jackets and put all electronic devices out in view (including getting your laptops out of their compartments).

As walked out of the 12-hour long plane ride between Singapore and Amsterdam, the twenty degrees centigrade difference in temperature hit me. Fortunately for me though (as I can’t stand being cold), the weather is not as cold as I thought it would be. Unfortunately, as I read on Financial Times on board, global warming has caused an unseasonably warm winter throughout the world.

Now I’m sitting here in Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport for an eight hour transit, working on lesson plans for my students this coming term that I should email to another lecturer so she can take care of my missing the first week of class at the university. The ‘communication centre’ is just across the void from where I’m sitting, but I have decided not to send the files to my colleague because it costs 3 Euro (US$4.25) to get 15-minute worth of internet time. Mind you, it costs nothing at Singapore’s Changi Airport for the same amount of time, and if you run out of time, you can still log in again for additional time, which is practically unlimited as long as no one is waiting for you. Meanwhile, a 15-minute worth of internet time costs only 20 Baht (US$0.70) in the more expensive internet cafes.

Suddenly I feel so poor, cold, and jet-lagged.

Un-halted stroll straight into the boarding area in Bangkok’s Suvarnabhumi Airport (even after the New Year’s Eve’s bomb), in contrast with going through two highly secured posts in Singapore’s Changi Airport: one right off from the plane (What were they thinking? That someone would bring a bomb all the way across continents without being noticed by security guards in other continents to bomb Singapore?) And another before going into the boarding area.

Or maybe I’m already spoilt by the laissez-faire attitude towards security in Bangkok – where I can just stroll in and out of places without once going through metal detectors or security checks that can be found in most of Jakarta’s places. But the security in Changi makes the ones in Jakarta look like a joke (which is true most of the time: they are just put up for shows only). At Changi, you would have to take off your jackets and put all electronic devices out in view (including getting your laptops out of their compartments).

As walked out of the 12-hour long plane ride between Singapore and Amsterdam, the twenty degrees centigrade difference in temperature hit me. Fortunately for me though (as I can’t stand being cold), the weather is not as cold as I thought it would be. Unfortunately, as I read on Financial Times on board, global warming has caused an unseasonably warm winter throughout the world.

Now I’m sitting here in Amsterdam’s Schiphol Airport for an eight hour transit, working on lesson plans for my students this coming term that I should email to another lecturer so she can take care of my missing the first week of class at the university. The ‘communication centre’ is just across the void from where I’m sitting, but I have decided not to send the files to my colleague because it costs 3 Euro (US$4.25) to get 15-minute worth of internet time. Mind you, it costs nothing at Singapore’s Changi Airport for the same amount of time, and if you run out of time, you can still log in again for additional time, which is practically unlimited as long as no one is waiting for you. Meanwhile, a 15-minute worth of internet time costs only 20 Baht (US$0.70) in the more expensive internet cafes.

Suddenly I feel so poor, cold, and jet-lagged.

The Peculiar Thai Way

On New Year’s Day, despite the bomb that blasted in parts of Bangkok and killed three people, the streets were still swamped by tourists and locals paying homage to the many temples of Bangkok. Not much difference with previous days, except that on New Year’s Day, there were many more people wearing yellow t-shirts walking around – making an interesting landscape of yellow subjects moving at different tangents in different speed across the urban landscape.

The Thais love their king so much that every Monday, the day that the king was born, they would put on something yellow (the Thai royal color) to express their love for the king. Pictures of the king in different occasions can be found the moment you step your feet on Thai’s ground, and in about every other house and public places you go. Most were of his pictures in royal suits waving from a balcony. Others were his trips to the countryside, sitting on the floor discussing matters with local officials, and even of him touching a homeless person.

This past New Year’s Day coincided with Monday, and the cityscape is especially swarmed with yellows. The picture below is taken in front of the Grand Palace on January 1, 2007.

Still related with the sense of paying homage to the royal family as well as to the kingdom, at precisely 8 o’clock every morning, most public places like the sky train and train stations would turn on the national anthem on loudspeakers. And instantly, all activities were put on hold and everyone would stand on pause until the end of the song when suddenly, as if someone has pressed the play button again, people resume their activities. The picture below is taken at the Hua Lamphong Train Station on December 20, 2006.

An interesting pause in everyday life of the city, often colored by shades of yellows, but especially more so on Mondays.

The Thais love their king so much that every Monday, the day that the king was born, they would put on something yellow (the Thai royal color) to express their love for the king. Pictures of the king in different occasions can be found the moment you step your feet on Thai’s ground, and in about every other house and public places you go. Most were of his pictures in royal suits waving from a balcony. Others were his trips to the countryside, sitting on the floor discussing matters with local officials, and even of him touching a homeless person.

This past New Year’s Day coincided with Monday, and the cityscape is especially swarmed with yellows. The picture below is taken in front of the Grand Palace on January 1, 2007.

Still related with the sense of paying homage to the royal family as well as to the kingdom, at precisely 8 o’clock every morning, most public places like the sky train and train stations would turn on the national anthem on loudspeakers. And instantly, all activities were put on hold and everyone would stand on pause until the end of the song when suddenly, as if someone has pressed the play button again, people resume their activities. The picture below is taken at the Hua Lamphong Train Station on December 20, 2006.

An interesting pause in everyday life of the city, often colored by shades of yellows, but especially more so on Mondays.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)